The

renowned contemporary artist David Hockney was born in Bradford (West

Yorkshire) in 1937. In the suburbs of Bradford, there is an art gallery,

Cartwright Hall, which Hockney used to visit in his youth. He said of this

place: “I used to love going to Cartwright Hall as a kid, it was the only place

in Bradford I could see real paintings.” He used to visit it as a schoolboy and

young student during the 1940s and ‘50s. In July 2017, the establishment opened

a new gallery dedicated to Hockney’s works. It was to see this that we set off

by bus (a ten minute ride) from Bradford to Lister Park in which the Hall is

located. What we found exceeded our expectations.

The

building of Cartwright Hall (as a purpose-built art gallery) was financed by

Samuel Cunliffe Lister (1815-1906), the son of a Bradford textile mill owner.

Lister became wealthy through the development of new and improved textile mill

technology. The house was named after Edmund Cartwright (1743-1823), an

inventor of various textile processing machines including one for wool combing,

which contributed greatly to Lister’s financial success. Modestly, Lister named

the Hall after the inventor rather than himself.

Lister

Park is extensive. It includes a fantastic feature, The Mughal Garden. If it

had not been for the miserable grey sky and the absence of the Taj Mahal, with

a little bit of imagination one might mistakenly believe that this garden was a

replica of the water features that the Mughals delighted in creating in what

became (in 1947) India and Pakistan. Opened in 2001, this garden, designed in

conformity with Mughal gardening convention, reflects the cultural affinities

of Bradford’s large South Asian community. This exotic-looking place, set

within a conventional British municipal park, is in harmony with the

multicultural range of exhibits within the Gallery.

The

neo-classical Cartwright Hall was designed by the architects JW Simpson and EJ

Milner Allen, both from London. Its interior is spacious, not in the least bit

stuffy or airless (as for example is the National Gallery in Edinburgh).

Stained-glass by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

We

began by looking at some of the works that Hockney might have examined during

his youthful visits. These include paintings by well-known artists such as:

Romney, Gainsborough, Reynolds, Vasari, Reni, and many of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Mingling with these, there are paintings by some of Hockney’s predecessors from

Bradford. One of these was Richard Eurich (1903-1992), the son of Dr Frederick

William Eurich (1867-1945). Dr Eurich, who arrived in Bradford from Chemnitz

(in Germany) aged seven, pioneered a method of cleaning wool so that it became

free of the deadly anthrax spores that had taken the lives of many wool workers

in Bradford. His son Richard studied at Bradford School for Arts and Crafts,

where Hockney also studied later.

Sir

William Rothenstein (1872-1945) attended Bradford Grammar School, where both

Richard Eurich and, later, David Hockney were pupils. He studied art at the

Slade School in London. He became a war artist in WW1. At least one of his war

paintings was on display. Rothenstein was a son of Moritz Rothenstein, one of

several Jewish entrepreneurs who came from Germany to Bradford in the mid-19th

century. These entrepreneurs played important roles in promoting the city’s

textile industry. William’s painting “Carrying the Law” has a particularly

Jewish theme. In the 1930s, William, by

then in London, hosted the Indian Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore, who

dedicated his collection of poems “Gitanjali” to him.

By William Rothenstein

This

brings me to something that I really liked about the Gallery. The paintings

(and stained-glass) by European artists, both well-known and not so famous, are

hung side-by-side with works by artists with South Asian heritage. This is done

so successfully that one does not feel that there is any cultural clashing

between them. It made me think how wonderful it would be if people of different

origins could coexist so harmoniously.

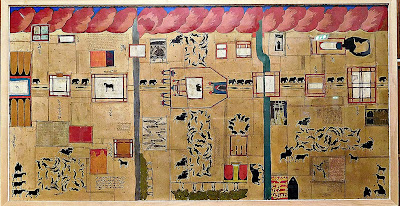

By Sylvat Aziz

The

South Asian artists, to mention but a few, include Jamini Roy (whose pictures

we did not see on display during our visit), Salima Hashmi, Arpana Kaur, Sylvat

Aziz, and Gurminder Sikand. In addition to these paintings, we saw one Indian

film poster on display. Just opposite

the main entrance on the ground floor, there is a reflective sculpture by Anish

Kapoor.

By Anish Kapoor

The

new Hockney Gallery is itself a masterpiece of gallery curation. It contains

some of Hockney’s earliest works done in the 1950s. These works, somewhat more

conventional than his later creations, show him as a highly skilled draughtsman

and artist. They portray his home town beautifully. The gallery also contains

some of Hockney’s more current work, including a series of paintings done

during one of his visits to his native Yorkshire. There is also one of his

famous swimming pool pictures. The gallery features a ‘recreation’ of one of

Hockney’s studios. This display includes a couple of the artist’s sketch books

and pads. I was particularly intrigued

by two publications on display, which were illustrated by Hockney: one was a

Bradford telephone directory, and the other a guide book to Bradford.

David Hockney: Self-portrait (1954)

Our

visit to the Cartwright Gallery was enjoyable, and left me thinking that even

if one saw nothing else in Yorkshire, this place is a ‘must’.

The

town of Saltaire is a short bus ride from Lister Park, and another mecca for

lovers of Hockney’s art. Before 1851, this place did not exist. It was built by

a benevolent industrialist Sir Titus Salt (1803-1876) as a model village for

the workers in his textile factory, Salts Mill, which neighbours it. The

place’s name derives from Sir Titus’s surname and the River Aire, which runs

close to the mill. The mill is separated from it by the Leeds and Liverpool

Canal. Saltaire is a well-preserved ensemble of Victorian buildings. It has been

designated a ‘UNESCO World Heritage Site’.

Salts Mill painted by David Hockney

Hockney

lovers might focus only on the enormous Salts Mill, but this is a mistake

because it would mean missing the fascinating little town, an industrial

forerunner of ‘idyllic arcadian’ garden suburbs and cities, such as those in north-west

London, Letchworth, and Welwyn. It is

also an antecedent of garden cities designed to house factory workers such as:

the Bata village at East Tilbury; Zlin in the Czech Republic; and Zelenograd

(i.e. ‘green city’) near Moscow in Russia.

Victoria

Street leads down towards the railway, the mill, the canal, and the river. The

upper section is lined with attractive stone buildings on one side. On the

other side, there is a rectangular green space, Alexandra Square, surrounded by

more buildings, alms-houses. The former ‘Sir Titus Salts Hospital’ (dated 1868)

stands where Victoria and Saltaire Roads cross each other.

Further

down the hill, we reach the Salt Building, which is marked as ‘schools’ on an

1889 map. It was a ‘factory school’. Mill owners were obliged by laws (passed after

1833) to provide their child-workers with education. Now a part of Shipley

College, it still serves an educational purpose.

Opposite

this architecturally whimsical building, there is a larger one set back from

the road. With two storeys of windows topped with circular arches and a

grandiose central doorway surmounted by a tower, this is Victoria Hall. This

was completed in 1871 for Sir Titus to the designs of Lockwood and Mawson.

Originally, it was an educational institute, but now its grand hall and other

rooms are also used for special occasions such as weddings.

The

Salts Mill stands almost at the bottom of Victoria Street. Ignore this for the

moment, and enter Albert Terrace. But, before doing so, you should take a look

at the Saltaire United Reform Church, which stands in its own grounds close to

the canal. This interesting Italianate

building with a circular tower mounted on a circle of Corinthian pillars was

built for Sir Titus in 1859, designed by Lockwood and Mawson.

Albert

Terrace runs along the lower ends of several steep streets where the mill

employees lived in houses of different sizes according to their inhabitant’s

ranking in the firm’s hierarchy. The streets are separated by the backyards of

the buildings on them, and between them the narrow back alleyways, which are

now crowded with ‘wheelie-bins’ used for placing domestic refuse.

Some

of the buildings on these streets are taller than their neighbours. These

housed lower-paid workers. Those houses between them, which have small front

gardens, were homes to foremen and supervisors. Senior members of the firm had

larger houses with bigger front gardens.

On

Titus Street, parallel to Albert Terrace but at a higher altitude, there are

small terraced dwellings without front gardens whose front doors open straight

out onto the pavement. These residences were the homes of the lowest paid

workers and their families. Although different classes of mill employees were

allotted different kinds of houses, all of them from the humblest to the

highest lived together in close proximity.

It is interesting that the founders of Hampstead Garden Suburb in North

London, where I grew up, tried to achieve the same social mixing. I do not

believe that it was ever achieved there.

The

school on Albert Road, now a primary school, has been present since 1893 if not

before. Near the south end of Albert Road at its meeting with Saltaire Road,

there is a stone building whose two sets of enormous doors are surmounted with

triangular pediments bearing weather-worn coats of arms. Now a restaurant, this

was formerly a tramway depot.

The

Salts Mill, the former textile factory, is now home to a huge exhibition of

works by David Hockney. This is arranged on three floors of the building in

what were once huge halls where William Blake’s ‘dark satanic mills’ churned

out the materials that made Bradford prosperous. Actually, this particular mill

seems to have been quite well-lit.

On

the lowest floor and the one above it, the walls are hung with works by

Hockney, mostly prints, but, also some paintings. Much of the floorspace in the

ground floor gallery is filled with tables containing merchandise for sale,

including, appropriately, artists’ materials. On the second floor, there is a

vast bookshop, also lined with works by Hockney.

The

uppermost floor is a huge exhibition space without merchandise. Its walls were

lined with Hockney’s pictures. They can be seen at their very best in this

spacious hall supported by cast-iron pillars. This gallery leads to a café,

where ‘light bites’ and drinks are available.

Beyond

the café, there is a permanent display of objects relating to the history of

Salt Mill. These include items such as: old factory equipment; examples of

textiles produced; a dental chair from the factory’s own dental clinic; and a

small fire-engine. On one wall there was an old notice informing workers what

to do if fire broke out. This was printed in English, Italian, and Polish. The

factory closed in 1986, long before Poland joined the European Union and the

recent influx of working people from Poland. The existence of the Polish

instructions suggests that even in the 1980s Bradford had a significant Polish

population. According to an article published on a BBC website (in September

2014): “In the 1940s it was immigrants from Poland who came to Bradford. They

viewed themselves as political émigrés so it was important to maintain a

national identity, traditional ideas, values and customs, all of which were

being suppressed in their homeland which was under Nazi rule.”

Some

decorative porcelain in the museum bears the crest of the Salts family. It

includes an alpaca, whose wool, combined with other animal’s fleeces, was an

important contribution to the prosperity of Sir Titus’s family. Near this display of porcelain, there is a

cleverly devised portrait of Sir Titus made using fabric from which pieces have

been removed selectively to produce the image.

We

did not eat at the café, but at Salts Diner on the floor with the

gallery/bookshop. The Diner’s menu cards and napkins are designed by David Hockney.

The diner’s walls are lined with the artist’s works. We ordered two dishes: a

smoked chicken with mango salad, and steak with chips and Béarnaise Sauce. We

washed these down with a lovely beer specially created for the Saltaire Diner.

Without hesitation, I can say that this was the best quality food that we have

ever eaten in a café or restaurant attached to a museum or gallery.

Napkin with a drawing by David Hockney

Although

there is no shortage of works by Hockney at the Salts Mill, I much preferred

the smaller but exquisitely curated gallery of his art at nearby Cartwright

Hall. However, a Hockney aficionado will be missing a great experience by not

making the trip ‘up north’ to see the Hockney exhibits just outside Bradford.

READ AND ENJOY BOOKS BY

ADAM YAMEY

ADAM YAMEY

Visit: http://www.adamyamey.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Useful comments and suggestions are welcome!